BUMPH. The knuckles on my right hand pressed into the side of my face in a steady rhythm. BUMPH. Scenes of thatched huts flashed by. BUMPH. A motorcycle with three passengers sped around. BUMPH BUMPH BUMPH. An insulted-looking goat scurried out of the way as we veered around potholes. Then a lull. The partial sun of the rainy season smeared itself across my window and I began to doze off again, the scenes of the past few seconds having already faded from consciousness.

But then, the rhythm changed. BUMPH BUMPH deBUMPH BUMPH deBAMPH. The potholes were coming more frequently now. I jolted awake, and realized the embassy van that was carrying myself and two colleagues to the town of Sokodé in central Togo had indeed found its destination. The outside scene had changed markedly. The flat, dusty terrain of southern Togo had been replaced in a matter of hours by undulating mountain ridges. They were close enough to feel part of the environment, yet far enough away to remain mysterious. More trees stretched their branches across the road as we entered the center of town. What little shoulder the road could boast of was lined with wooden stands loaded with mangos, papayas, and banana bunches. Several turquoise-painted houses sat opposite the hotel grounds where we now stopped. Overall, I felt an immediate change of atmosphere in this place, and couldn’t wait to get started on the purpose of the trip.

My colleagues—one focusing on university admissions, the other on American Corner enhancement—and I had travelled ‘upcountry’ on a diplomatic mission of sorts. We had come to meet with members of the English-learning community, from teachers to students to officials known as ‘Inspectors.’ We all had different goals. My personal mission was to meet as many people as possible who are involved with English instruction in the city. I would introduce myself to them, and find out how we could work together in the future for English teacher training and encouragement. I plan to spend several months in these two towns when I return for my encore year in Togo.

The Hotel Central greeted us warmly in the fading light. Later that night, however, was an entirely different story. I woke up to the sound of the roof caving in. Actually, it was just that an extremely enthusiastic rain—the kind to do a rainy season proud—had burst upon the town and was doing its best to pummel the top of the hotel. Thankfully for us, the structure had seen the likes of this before, and merely smirked as the torrents beat down on the top of the flat roof. But this was too logical for my half-awake thinking. It sounded like the roof was caving in and we’d soon be swimming out of our second-floor rooms. I even pulled on my jeans in case we needed to flee the floodwaters. Then a bolt of realization shot through my mind like the flashes of light outside—the roof was made of tin. On top of that, just outside my door was a brick lattice—an open air brick lattice. I was hearing the sound of the rain on the flat tin roof combined with the sound of a storm you hear when you’re out camping. Never has knowledge been so sleep-inducing. I fell back into bed and knew nothing else until a nearby rooster crowed at 4am.

If the atmosphere of Sokodé had immediately attracted me, our first meeting with an English inspector placed a seal over my infatuation. My colleague Basile and I climbed in the embassy van early the next morning, and went in search of that gentleman’s headquarters. After much turning and braking through all manner of grassy lanes and rocky roadways, we found the office of Mr. Sahido. It was nestled under two magnificent mango trees and built up on a platform of sorts, then fronted with a staircase that wound its way up towards the door. After entering, and introducing ourselves to two startled assistants, Mr. Sahido himself came tottering out of his office. He stood about half a foot shorter than myself, stretched a wide smile underneath deep brown eyes, and was attired in head-to-toe pumpkin orange.

“Welcome! So happy to see you,” he exclaimed, his arms spread wide.

The rest of our conversation went just as pleasantly. Mr. Sahido repeated over and over to me how glad he was that I was there, as foreigners usually stay in Lomé. At this, I shifted uncomfortably in my seat—I’d been in Togo for seven months. However, his tone was never self-pitying. He focused on the present. We went on to discuss the challenges of teachers in his town (the most pressing being, unsurprisingly, class sizes of around one hundred each), and I asked him what particular topics he’d like me to discuss when I return.

“Definitely, I want them to learn how to speak more communicatively.”

I about swallowed my wintergreen tic tac. This was the first time I’d heard an official use this word without prompting. This concept had been my touchstone since I came to Togo—my spotlight, my soapbox, my baby. It means focusing on whether students can communicate in English for daily tasks, not just rattle off the past participle form of a verb in an academic setting. It runs extremely counter to how the language is currently taught. Though, obviously this was changing—and apparently there was hope.

What followed was a conversation that I enjoyed immensely. Mr. Sahido and I went on to speak conspiratorially as if we were long-lost friends—about English teaching, slacking students, even the heat. He made jokes often, the laugh lines near his eyes stretching to his ears each time he particularly amused himself. He even gathered a few loitering teachers into his office and had us take a group photo.

Before long, however, Basile and I had to head to our next appointment, so Mr. Sahido followed us outside. After a couple of hearty handshakes, and some careful maneuvering by the driver to avoid an impressive pile of rocks, we were off.

The rest of the day was spent meeting other teachers at nearby schools. Basile spoke about several scholarship programs being offered by the embassy, and I continued to suss out places and people I could work with in the fall.

At one point, we made a wrong turn into what we thought was a high school, which turned out to be an elementary school. Our mistake was immediately apparent.

That evening, I met up with the leaders of Sokode’s chapter of the Togo English Teachers Association. We discussed some of the challenges facing English teachers there and what sorts of events I could sponsor when I return. We met on the top of our hotel for some pizzas and drinks. As we spoke, I listened to the traffic hurtling through the streets below us. The sky’s star-studded clarity spread a wide canopy overhead.

The next morning, the embassy van turned north towards Kara. Though a bit smaller than Sokodé, and less populated, it has been more developed than other cities in Togo and thus is widely considered the country’s second city. The fact that the current president’s family hails from Kara doesn’t hurt its status either.

As we drove northward, the scenery became quite spectacular. The foothills of Sokodé gave way to mountain peaks and narrow passages through blue-green forests. Several times we rounded a sharp curve where there was no barrier—only a jaw-dropping view of a fertile valley far below. Rock outcroppings jutted from the sides of the mountains. Even up this far, the embassy van was required to veer around the occasional loitering goat in the road.

In Kara, Basile and I had a great time visiting several local schools and meeting the always disarmingly friendly students.

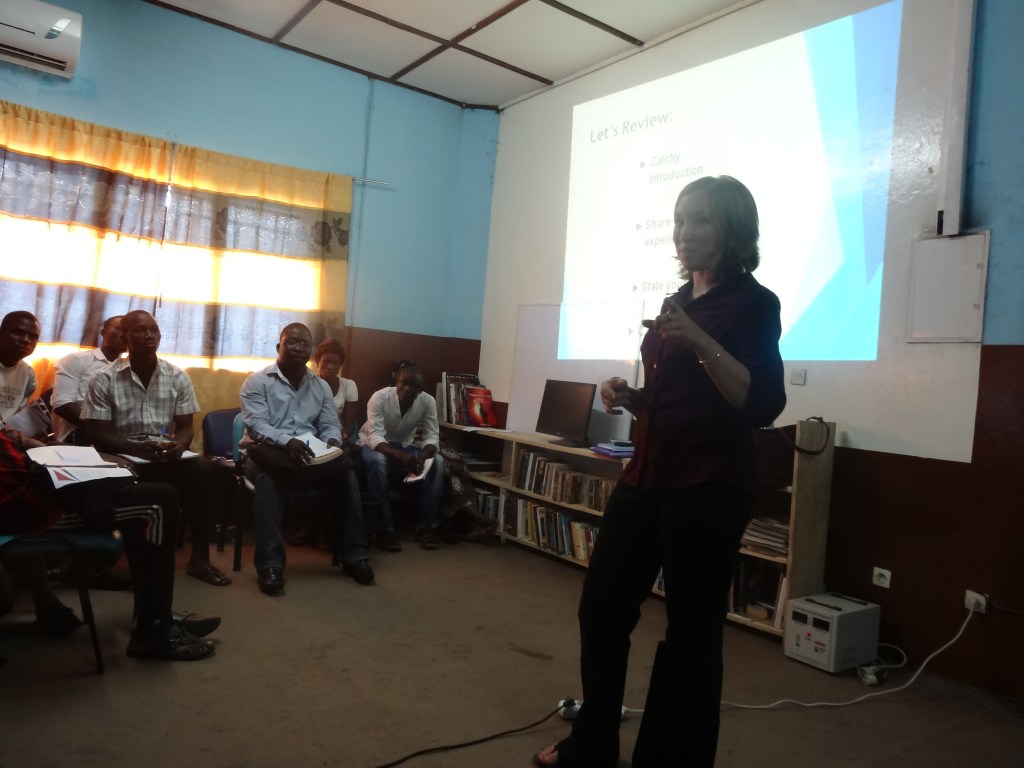

We also presented at Togo’s second American Corner location about studying in the U.S.!

Finally, we had one last place to visit before heading back to the hotel. It was a home for children that have been physically and sexually abused. A small team of volunteers run the place like a temporary home-slash-school for the children until they either find other relatives for them or they can be adopted to new families. After getting out of the van, we followed our friend down a narrow passageway between two tan buildings. At the end of it, the space opened up to a little courtyard where about twenty children began to scramble out of a nearby room and seat themselves on three rows of wooden benches. While most smiled shyly at their visitors, one small boy in a bright blue shirt bounded up to me. Raising milky-brown eyes to mine, he seized my hand. After slowly turning it over once, twice, he wove his small fingers around mine, before planting a dusty kiss on the top. He looked up at me again, this time with a blinding smile. Under the dust on his face I took in a nose that looked out of joint, as if from some past trauma.

At that moment, one of the teachers waved him back to the group, and he scuttled away as the others sharing their favorite song with us. Each child’s face was turned towards the sky in cheerful abandon as they gesticulated to the music.

Ah, I thought, reminicing on the last few days as well as the present afternooon. This is why I’m in Togo.